Writing

My writing explores the intersection of psychology, ecopsychology, and neuroscience. Through my Substack I explore how we might expand our perspective, deepen our capacity for compassion, and maintain our center in an increasingly complex world. My work weaves together scientific research and accessible insight, examining questions of mental health, wellbeing, and what it means to flourish as human beings. Subscribe to receive new essays in your inbox.

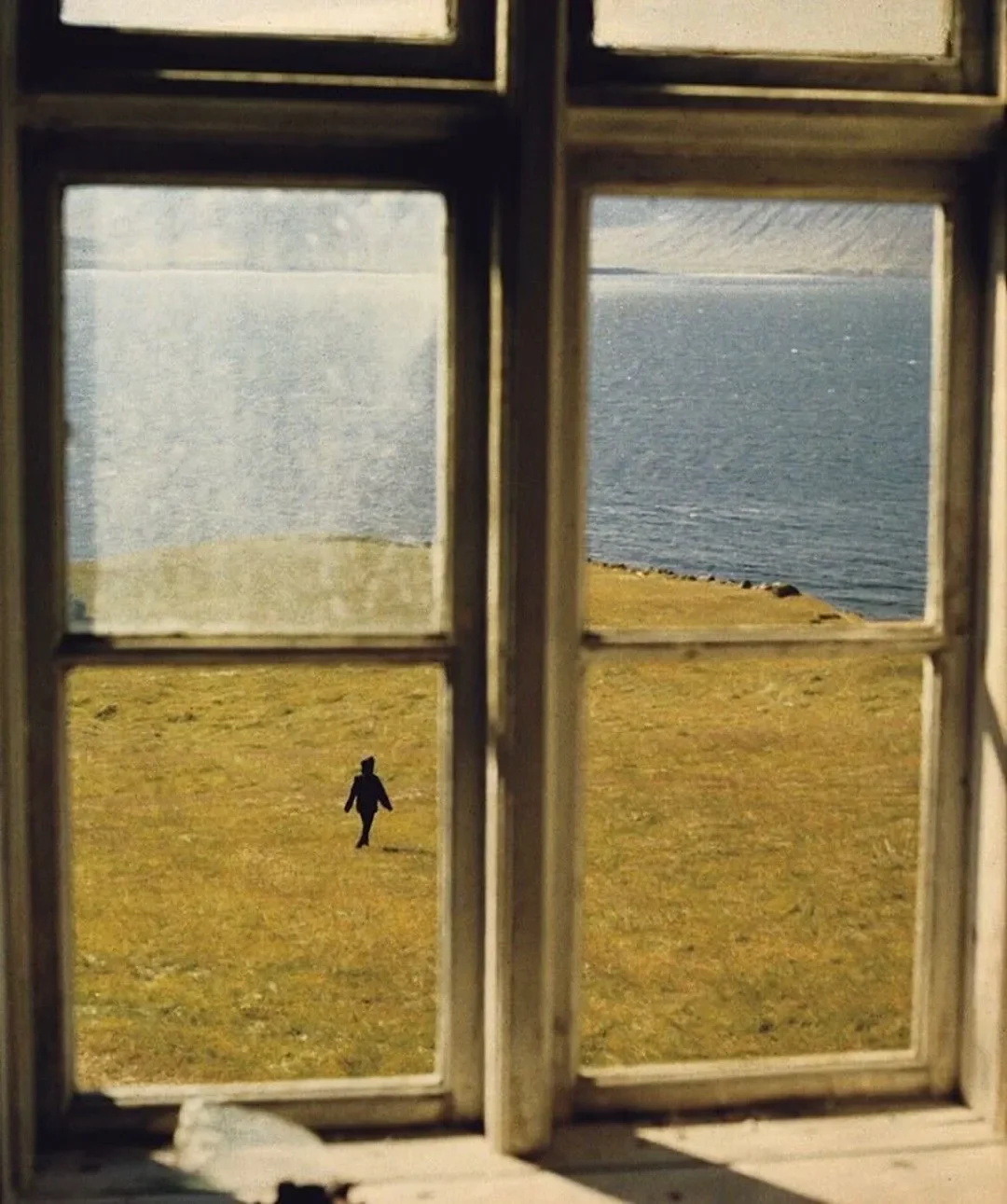

How Nature Helps Us Widen Our Lens

When stress settles into the body, our minds instinctively narrow, creating a measurable shift in how we perceive the world. Research shows that under pressure, our field of attention contracts. It’s as if the brain begins to tighten the lens on its internal camera. We become preoccupied with the immediate: the next task, the latest crisis, the loudest worry. Meanwhile, the broader view slips away. This reaction is part of our evolutionary wiring. It helped early humans survive, but in modern life, where stress rarely signals actual danger, this narrowing can keep us trapped in a cycle of urgency. We lose access to the part of ourselves that sees clearly, thinks flexibly, and responds with wisdom.

This response is not only psychological, it’s also biological. Stress activates the amygdala and reduces activity in the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain that governs regulation, self-awareness, and complex decision making. One study published in Scientific Reports found that people experiencing acute stress showed significant narrowing of visual attention. In other words, they literally saw less.

The good news is, the natural world offers us a way to widen our view.

When we look out over an ocean, follow a hilltop path, or linger in a wide green city park, it can expand both our visual field and our mental state. When we look out toward a horizon, our bodies begin to calm. Our thoughts stop racing. Breathing slows. We remember that life is more than this one moment of stress.

A Conversation: Nature Deficit Disorder, Awe, and the Small Self

Researchers at UC Berkeley wanted to know if awe could change human behavior. They brought study participants to a grove of towering Tasmanian eucalyptus reaching 200 feet tall, some of the tallest hardwood trees in North America. Participants were asked to stare upward at the trees for one minute. A control group, standing in the same spot, stared at a tall building instead. Then a researcher “accidentally” dropped a box of pens. The people who had been looking at the trees picked up significantly more pens. They were more helpful, more generous, less entitled. One minute of looking at something vast and beautiful had literally changed how they treated a stranger.

This is what awe does to us, and currently, humanity is starving for it.

I recently sat down with the Bets Life Podcast for a conversation that went places I didn’t expect. We talked about the science of nature and the brain, yes, but we also got into personal territory. How I ended up on a one-way flight to Hawaii at twenty years old with no plan. The spiritual community I was raised in that most people in my life don’t know much about. What I learned from losing my mother at four. The messy reality of screen time with my own kids. If this sounds interesting, you can listen to it here.

The podcast got me thinking about something I want to expand on here, because the science of why nature changes us is far more profound than most people realize, and the cost of our indoor lives is showing up everywhere.

Going Green Made Me Happier - The Psychology and Neuroscience of Environmental Action

Being environmentally conscious does more than just protect the planet, it profoundly benefits our mental health. Engaging in eco-friendly behaviors, such as reducing waste, planting trees, or conserving energy, may activate the brain’s reward pathway, with research suggesting this is associated with dopamine release and generating a sense of happiness and purpose. Acts of environmental stewardship also engage the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), a region associated with decision-making, emotional regulation, and self-reflection. This enhances self-efficacy, or the belief that our actions have an impact, which reduces feelings of helplessness, anxiety, and depressive symptoms.

Aligning our behaviors with our values fosters what researchers call cognitive coherence, which supports emotional stability. When our actions contradict our environmental values, we experience cognitive dissonance, activating the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), a brain region linked to distress. Aligning our daily choices with our beliefs prevents this tension, promoting mental clarity and emotional well-being.

A major psychological challenge in environmental consciousness is eco-anxiety, the distress caused by awareness of climate change and ecological destruction. Neuroscience shows that persistent worry about the state of the planet can activate the amygdala, the brain’s threat detection center, leading to increased stress responses, hypervigilance, and even symptoms similar to generalized anxiety disorder. Chronic amygdala activation can disrupt the body’s stress response system, leading to heightened cortisol levels that affect sleep, mood, and overall mental health. Additionally, repetitive negative thought patterns, or rumination, engage the subgenual prefrontal cortex, a region linked to depression. To prevent this, it’s crucial to use strategies that shift brain activity from fear-based circuits to those associated with problem-solving, resilience, and well-being.

What Spending 93% of Your Life Indoors Is Doing to Your Brain

You are not separate from nature. You are nature. I will keep saying this until the end of time because it. is. so. important. to. understand.

Spending time outside fundamentally changes how your brain and body work. The research on this is decades deep in the fields of ecopsychology, neurobiology, and environmental medicine. The effects show up in every system we know how to measure.

A wave isn’t separate from the ocean. You’re not separate from the Earth. The more we attune to the natural world, the more we find ourselves again.

Somewhere along the way, though, we forgot this. We built walls and screens, climate-controlled spaces and artificial light. Traded dirt under our fingernails for notifications on our phones. Our bodies are still wired for grasslands and forests and have registered the severance as loss.

The biology of belonging

When we talk about disconnection from nature, we’re not being metaphorical. The separation shows up in measurable ways: nervous system dysregulation, compromised immune function, mental health struggles.

Back in the 1980s, environmental psychologist Roger Ulrich discovered something that should have changed how we think about healing. Hospital patients recovering from surgery got better faster, needed less pain medication, and went home sooner when their rooms looked out on trees instead of brick walls. Not slightly faster. Significantly faster.